“I think Spain is terrible. You know, they’re doing very well, the economy is doing very well, but that could disappear in a heartbeat if something bad happened.” Those were the ominous words that Donald Trump directed at Spain last June. Either by chance or by design, he hit the weakest point of the collective consciousness of our country: our lack of faith in the strength of the Spanish economy. We Spaniards take for granted that the next macro collapse could be just around the corner; and if we wonder who the first victim will be, the construction sector is always among the candidates. But how likely it is that the current reawakening of new housing construction will “disappear in a heartbeat”?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Josep Ramon Fontana

ITeC

Construction market analyst and ITeC’s representative in Euroconstruct, which is a vantage point from which to observe the rollercoaster movements of the sector.

In recent years, the conditions have been favourable to new residential construction: cheap credit, low or very low stock levels, substantial demand, and robust levels of sales. But somehow, developers chose not to take risks. According to the housing starts statistics, they have been pouring into the market 107 thousand dwellings per year with the consistency of a metronome from 2018 to 2023, except for the drop in 2020 caused by the pandemic. For the purposes of this briefing, we will call it the “normal” housing production level.

If we stick to this definition, then 2024 has been an “anormal” year with almost 128 thousand starts. Such an increase must look shocking for an external observer, but in Spain it has been received with a nonchalant attitude. Considering the state of the market, those 128,000 starts do not seem out of place; what was really incongruous was keeping production below 110,000 units for so long. The main risk is production capacity: finding contractors and workers can be much more difficult than finding buyers for the finished product.

But as Donald Trump has warned, Spain has this rare ability to grow on top of fragile foundations. Just to be sure, we should look for cracks in the current state of the residential pipeline after the shift in 2024.

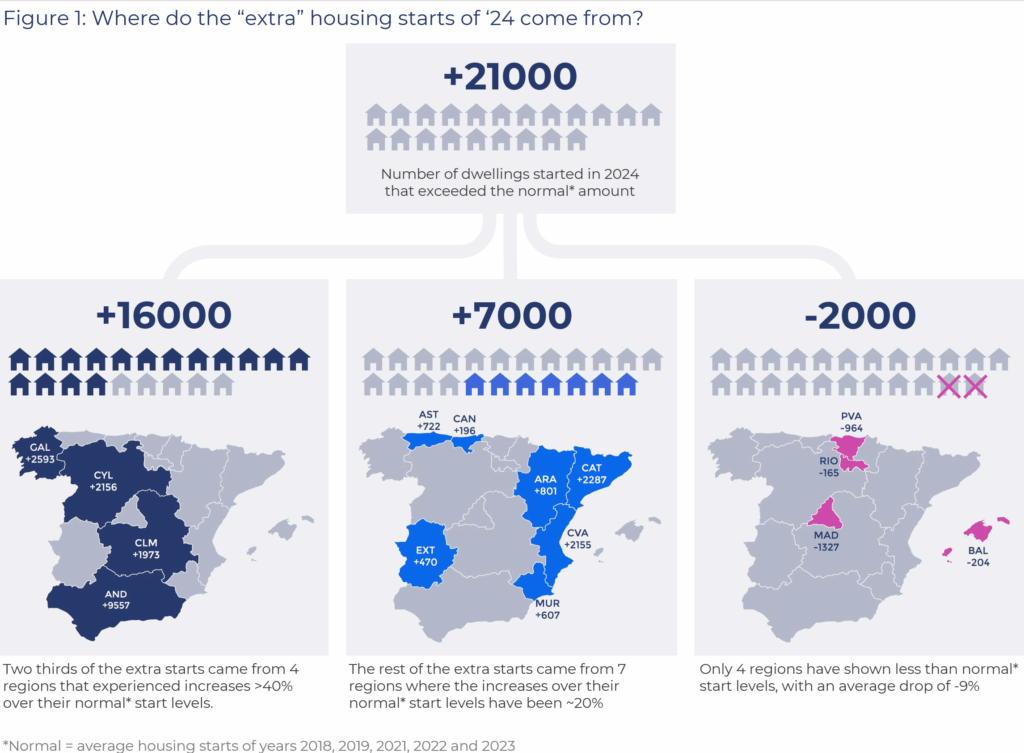

We can begin by checking the geographical distribution of the housing starts granted last year. If the extra dwellings have been evenly distributed throughout the territory, that can be considered a good sign, even if it is just a case of safety in numbers. But if the growth is driven by just a handful of regions going off into a construction frenzy, then we should raise red flags. The reality is something in between:

The good news is that almost all the regions have taken part in this change of pace. Only four regions have underperformed if we compare their housing starts in 2024 with the average of the 2018-23 period, although we should notice that the Region of Madrid (with 15% of the national population) appears in this list. The not so good news is the overperformers: four regions that have generated two thirds of the “extra” housing starts of last year, while their share of the population census is just one third.

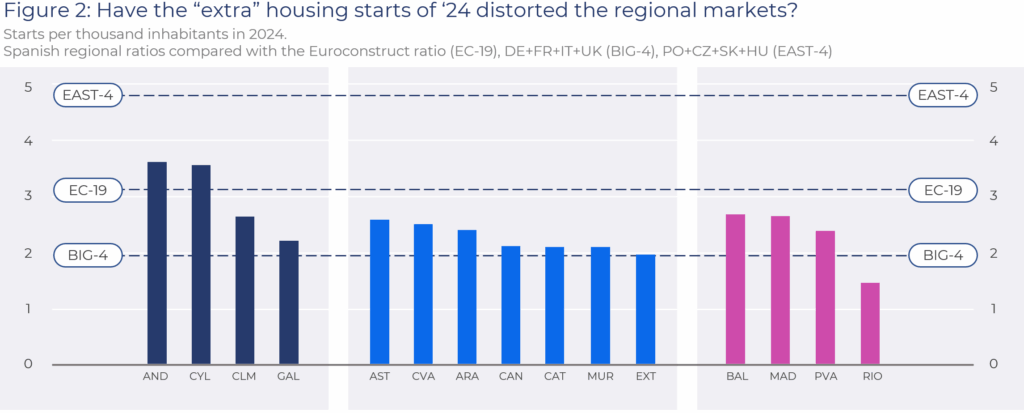

This confirms that the housing pipeline has accelerated aggressively in some regions. The next question is whether it has conducted these markets towards exaggerated production levels. We can use some references from the rest of Euroconstruct countries as a benchmark:

Only two regions surpass the Euroconstruct (EC-19) average of 3.1 starts per 1000 inhabitants: Andalucia (3.6) and Castilla y León (3.6). We should also be aware that the EC-19 ratio of 2024 is rather a low bar in comparison with its peak at 4.0 back in 2018-19. If we exclude these two regions, the rest of the country is dealing with 2.6 starts per 1000 inhabitants, which is quite similar to the 2.4 mark that results from aggregating Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom. In conclusion, the Spanish housing pipeline has made quite a jump forward in 2024 but, since the 2023 levels were very modest, there are no signs of an abnormal situation from the supply side.

“This new phase of housing makes market sense, but before becoming the new normal, it has production bottlenecks to overcome.”

We may have real cause for concern if this kind of growth in new residential projects is sustained over time. Our scenario in the last Euroconstruct report in June contemplated that housing starts will keep increasing this year, but not as much as they did in 2024. The forecast was 135,000 units, which is 7,000 more than 2024, and after receiving the data for the first five months of 2025 it still seems a realistic goal. But this promising outcome is becoming blurred by the flood of headlines that are again sounding the alarm on a new housing bubble. There is no doubt that the residential real estate market is under genuine strain in Spain, with steep growth in housing prices, but to anticipate a replay of the 2007 crash is just bloodthirsty journalism. Right now, there is no speculative lending pumping up risky debt and (most crucially for construction) there is no oversupply. In fact, the housing deficit is so evident that the authorities are attempting to resuscitate public housing construction after a very long period of paralysis. All things considered, we have no reason to accuse Spanish residential developers of recklessness, and no reason to expect the kind of cataclysm that Trump heralds in every country that does not play by his rules.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Josep Ramon Fontana

ITeC

Construction market analyst and ITeC’s representative in Euroconstruct, which is a vantage point from which to observe the rollercoaster movements of the sector.